Customer Services

Customer Support

Desert Online General Trading LLC

Warehouse # 7, 4th Street, Umm Ramool, Dubai, 30183, Dubai

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

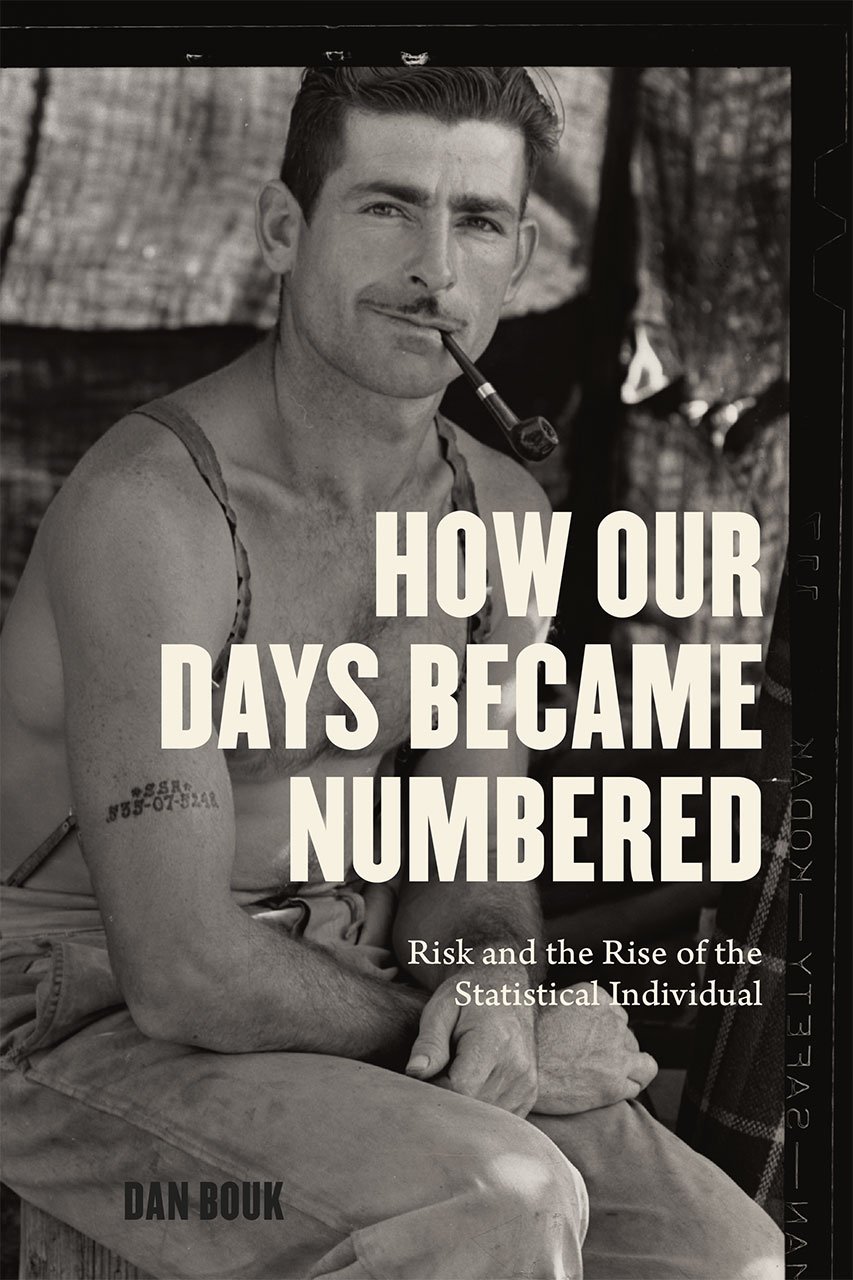

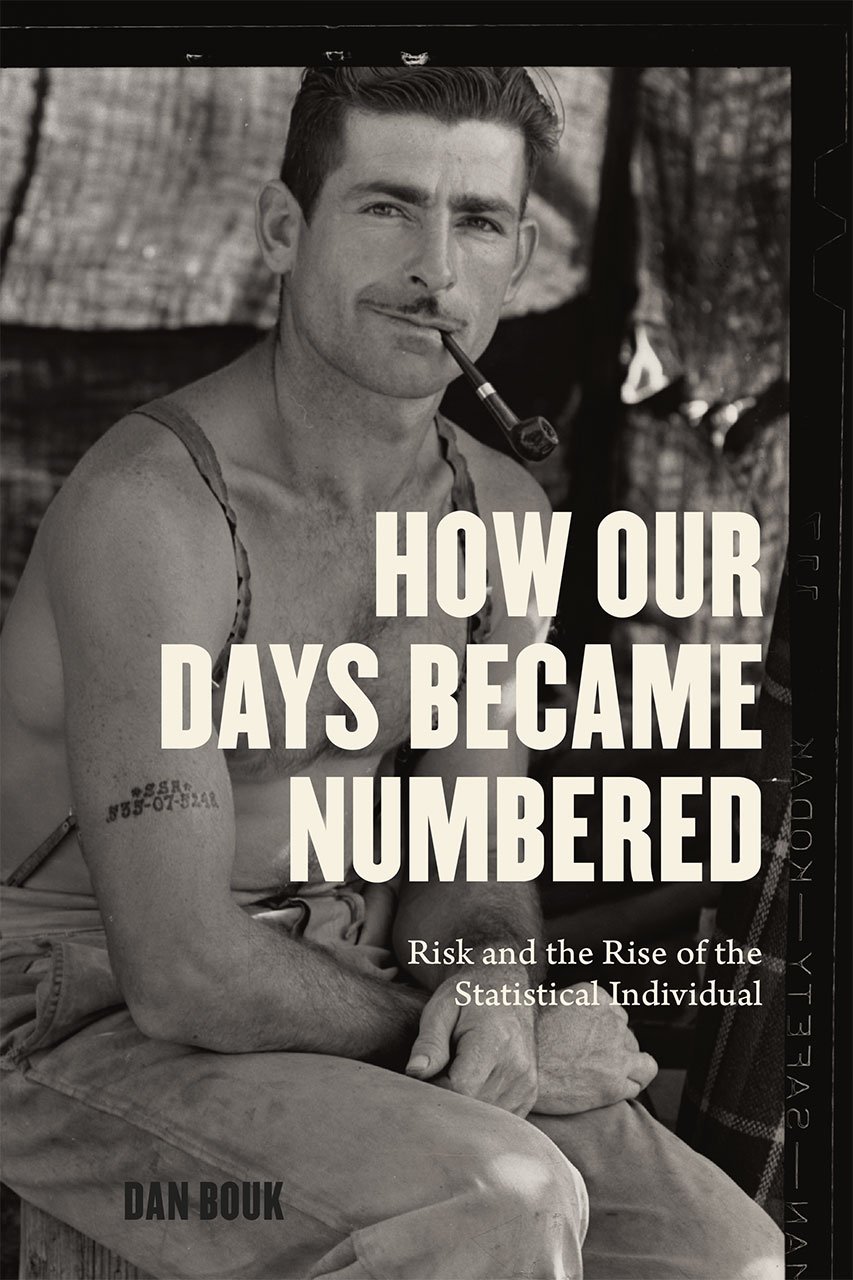

Full description not available

Trustpilot

2 months ago

2 days ago

1 day ago

2 weeks ago